by Antonia Bale

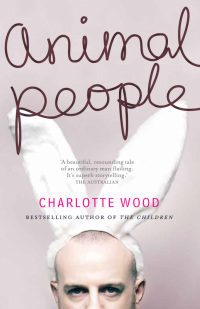

The Australian has described Charlotte Wood as one of that country’s ‘most original and provocative writers.’ She is the author of five novels and two books of non-fiction. Her latest novel, The Natural Way of Things, won the 2016 Stella Prize, the 2016 Indie Book of the Year and Novel of the Year, and was the joint winner of the Australian Prime Minister’s Literary Award for Fiction. It has been published in Britain and the US as well as many countries in Europe. In 2016 Charlotte was named the Charles Perkins Centre’s inaugural Writer in Residence at the University of Sydney.

In July, MA and PhD prose and poetry students at the IIML were lucky enough to take a masterclass with Charlotte on building urgency and pressure. Unfortunately Charlotte then lost her voice and was unable to appear at Te Papa for her planned ‘Writers on Mondays’ reading and conversation. This interview is in lieu of that event. MA student Antonia Bale speaks with Charlotte about language, experimentation, Pinterest and writing what you want to write.

Place plays an obviously strong role in The Natural Way of Things but it’s also something that really influences the narrative in Animal People and, to a lesser degree, The Children. Is place a starting point for you?

It can be, and definitely was with those three books, even though the place in The Natural Way of Things wasn’t a real place but a kind of dreamy (some would say nightmarish!) no-place. I do find that establishing a setting fairly early on helps me develop characters and plot, because once I have a place I can have my people responding to it, pushing against it, and often, being trapped in it with problematic others. Which can bring about useful frictions and conflicts. What I mean is that if I have a place in which to see the people of my story, I really need almost nothing else to begin a novel. This is comforting if, like me, you are the kind of writer who doesn’t plan from the beginning.

It can be, and definitely was with those three books, even though the place in The Natural Way of Things wasn’t a real place but a kind of dreamy (some would say nightmarish!) no-place. I do find that establishing a setting fairly early on helps me develop characters and plot, because once I have a place I can have my people responding to it, pushing against it, and often, being trapped in it with problematic others. Which can bring about useful frictions and conflicts. What I mean is that if I have a place in which to see the people of my story, I really need almost nothing else to begin a novel. This is comforting if, like me, you are the kind of writer who doesn’t plan from the beginning.

The Natural Way of Things traverses some dark territory– misogyny, how women who speak out about sexual abuse are treated, the media’s role in this – and yet the way you use language in the book is strikingly lyrical and beautiful. You’ve said that you felt that this came about as a response to the darkness in the novel. Can you talk to us a bit more about how you see the relationship between subject matter and language use?

It’s not really a very conscious decision, I have to say, but at a certain point in writing The Natural Way of Things I could see that I was constantly drawing beauty into the story as a way of balancing the ugliness – the moral and spiritual ugliness – of the material. The language in that book is much lusher, much more lyrical than, say, in Animal People. I don’t know if it would work terribly well if I were too conscious of this at the start – it could end up a sort of mechanistic approach, when what you want is for the language to merge very naturally with and arise from the story you’re telling. But I guess the overall point is that stories need light and shade, and with such a dark story, it seemed essential – for me as the writer, as much as the reader – to allow in as much ‘light’ in the form of beauty, and the potential for my girls to perceive beauty – as possible.

At the same time, too much beauty is a dangerous thing in a book. When I was first writing, I mostly relied on the beauty of language to stand in for the absence of other things like plot and strength of ideas and narrative tension. It didn’t work – too much lyricism ends up just making the prose claustrophobic and self-conscious. So now if I feel myself tipping into an overindulgence in the luxury of language, I try to punch a few holes in it with a bit of ugliness or plainness.

The Natural Way of Things is very different from your previous books. You’ve said that while writing it you really didn’t think anyone would read it. And yet, it has become a breakthrough book. Can you reflect on what this might mean for writers and their relationship to readers? Should writers write what they most want to write and trust that readers will get it?

They most definitely should write what they want to write – but this is tricky territory, because ‘wanting’ is hard to define. I didn’t want to write the book I did, for example! I found it frightening and dark, and while I don’t want to be too dramatic about it, I felt I was entering some really quite horrible part of myself that, at times, felt almost dangerous to engage with. So, I really resisted the darkness of it, and kept trying to write around it, and to make it into a ‘nicer’ book. But that didn’t work at all, so only when I stopped resisting its nature did it begin to work. And once I got the first draft down, then I thought, okay: now make it into art. That’s where the beauty and the hope can come in, from turning a mass of ugly material into a shapely work of art.

I think you have to be honest in taking the big risk of this, because it’s more than possible that you can do all this – be yourself, write what you want to write, trust the reader – and then not be rewarded with readers or praise. It happens all the time. There is absolutely no guarantee that readers will follow you wherever you want to go. But that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t do it, because what is an artist here for, if not to pursue her own creative instincts?

I discovered with The Natural Way of Things something I had sort of intuited before, but hadn’t really had to rely on: that if you pay close enough attention, and listen to your instincts, a book will tell you how to write it. You have to yield enough to it, and have the humility to accept that you can obey this and still fail. It’s scary! But when the rewards do come, they are so thrilling. You learn a lot about yourself, too.

In your interview with Margo Lanagan for The Writer’s Room you said the scrapbooks she makes for her work appealed to you at a ‘non-verbal, gut level’. You used Pinterest in a similar way to gather images to help you imagine the future world of The Natural Way of Things. What did this approach lend you and how did it influence the tone or language of the book?

In your interview with Margo Lanagan for The Writer’s Room you said the scrapbooks she makes for her work appealed to you at a ‘non-verbal, gut level’. You used Pinterest in a similar way to gather images to help you imagine the future world of The Natural Way of Things. What did this approach lend you and how did it influence the tone or language of the book?

It was really useful. Seeing Margo’s beautiful scrapbooks inspired me to be more organised about collecting images as triggers and inspiration, which I had always done in a haphazard fashion. Pinterest turned out to be the perfect way for me to collect them, for that book – I’m doing it again now, but so far it’s not proving as useful, so maybe it depends on the book. I made sure it was a ‘private’ board so nobody but me could see it, and then I set it as my computer’s home page whenever I opened the internet. After a while of just collecting images very instinctively, I saw that the colours were mostly complementary, that there was a mood being created by the sombreness (and occasionally downright creepiness) of the images. There was a tonal cohesion to the images that was somehow consoling, even when the book was a total mess. One of the things that’s useful about it, and Margo said the same thing I think, is that it’s a good way of plunging yourself into the mood of the book very quickly.

Margo said this about her images: ‘They’re particularly good for when you get called away from the project and you lose contact with it. If you want to get back into the feeling of it, something like this is much quicker and stronger than reading through the draft that you did and the notes that you’ve made.’

If anyone’s interested, my The Natural Way of Things board is now public – it’s pretty creepy though, so be warned!

Your novels are considered ‘realist’. However, there’s a slightly mysterious presence in Margaret’s car in The Children and in The Natural Way of Things Verla’s fever dreams bleed into her waking life. What does departing from strict ‘realism’ give you as a writer?

It gives you everything. I mean, it allows so many more possibilities – Amanda Lohrey was the writer who crystallised this for me, when she told me in our Writer’s Room interview that she doesn’t trust any novel that doesn’t contain what she called ‘a message from another realm’. We were talking about dreams, and she said that while lots of readers hate them, they can bring in another layer of meaning into a book, and I completely agree.

I don’t know about you, but I feel that a huge part of my life, and my ‘selfhood’ for want of a better word, exists on some other plane than the visible and the tangible. Our thoughts, memories, dreams, anxieties, our relationships, our sense of ourselves, often have very little to do with what can be identified as the ‘real’, concrete world.

I don’t know about you, but I feel that a huge part of my life, and my ‘selfhood’ for want of a better word, exists on some other plane than the visible and the tangible. Our thoughts, memories, dreams, anxieties, our relationships, our sense of ourselves, often have very little to do with what can be identified as the ‘real’, concrete world.

It could be because I was raised in the Catholic religion, which quite apart from all the nonsense is full of a very rich sense of mystery, that not to acknowledge this sense of the unknown, the dreamy, the ‘supernatural’, feels to me that I would be ignoring an enormously important part of life. And so to ignore it in fiction seems madness.

From a technical point of view, it’s also a very helpful way sometimes of creating the unease, or the sense of tension and suspense, that helps to propel a reader through the pages. As Lohrey said, ‘small, unorthodox manoeuvres can have potent effects’.

The characters’ names in The Natural Way of Things – Verla, Yolanda, Teddy, Boncer, Maitlynd, Hetty – jump out off the page. They’ve got a kind of moxie about them. They’re quite different to the Geoffs, Cathys, Margarets, Stephens and Fionas of The Children and Animal People. Are names a way in for you in terms of creating character?

It’s very strange – the names in The Natural Way of Things just pretty much arrived out of the blue and did not change (apart from some of the peripheral girls, whose names took longer to settle upon). Again, after the fact, I could see that these quite strange names were part of the feeling of otherworldliness of that book – whereas with the previous two novels, I wanted a very real sense of ordinariness, of familiarity. I wanted the Connolly family to feel almost already recognised by the reader, so the familiarity of the names were a part of that.

None of these decisions are so conscious at the time.

I remember my friend the writer Tegan Bennett Daylight talking about character names way back when we were both baby writers, and how sometimes in writers’ early books characters have very beautiful names, or very dignified, quirky, whimsical sorts of names. You know, nobody’s called Alan. Or Sharon. It’s as if you’re naming your first baby. And Tegan said that if you’re not careful, the characters’ names can ‘stink of your ambition for the book’. I thought that was very astute, and I’ve tried to remember it. Although with The Natural Way of Things I obviously abandoned that altogether!

You’ve said that you chose to set Animal People in a single day as a kind of technical experiment. What other technical experiments have you set yourself? How has this influenced your writing?

It’s helped, sometimes, to have this idea of a technical mark to aim for. With The Children I wanted to push myself on the drama side of things, to get a bit more suspense and tension into my work. Animal People was the one-day experiment, and in The Natural Way of Things I wanted to play around with reality, allowing myself some speculative, non-realist experimentation. With my new work in progress I’m having a shot at a more complex and rather old-fashioned use of omniscience or shifting points of view, but I don’t think it’s working very well. We shall see! Sometimes the technical and craft elements of writing are consoling things to focus on when other parts aren’t working.

It’s helped, sometimes, to have this idea of a technical mark to aim for. With The Children I wanted to push myself on the drama side of things, to get a bit more suspense and tension into my work. Animal People was the one-day experiment, and in The Natural Way of Things I wanted to play around with reality, allowing myself some speculative, non-realist experimentation. With my new work in progress I’m having a shot at a more complex and rather old-fashioned use of omniscience or shifting points of view, but I don’t think it’s working very well. We shall see! Sometimes the technical and craft elements of writing are consoling things to focus on when other parts aren’t working.

In terms of its influence on my work, I’m not sure exactly what effect it has had – I have always had a horror of repeating myself, and wanted to do something quite different with each book. So I guess it has pushed me into new terrain, so far. But the more books you write, the harder it is not to repeat yourself, and I’ve become interested lately in the way visual artists quite often seem to even cannibalise their own earlier work to make new work – they don’t have the same kind of shame about this that writers have (or at least this writer). So I might be relaxing my views on this!

It was such a delight to revisit the Connolly family from The Children in Animal People. What was it like writing a book about a character that you (and readers) already had some context with? Did you consider this a creative constraint? Is it something you’d consider doing again?

It was fun to do that, almost a sequel but really a completely independent book. I found that having the main character of The Children – Mandy – completely offstage and absent in Animal People – gave me enormous freedom to basically start again, yet have glimpses of the family here and there. In one way it was a constraint to have the same characters I guess, but not really, because I thought about it as a completely new book with completely new characters. I just had to re-make them in a new context.

I once said I’d never write about Stephen or that family again – but a very astute bookseller challenged me to write about Stephen in, say, 20 years’ time. Who knows, maybe I will!

In both Animal People and The Natural Way of Things the ending offers something akin to hope or salvation. Is this part of what you think an ending could or should do?

Hope is an interesting ethical position, and an expression of who you are as a writer. In general, I vote for optimism over despair. I think I’m actually a fairly pessimistic person, but I do see hope as a moral position – if you give up on hope you abandon the possibility of change, and that is a very, very dark place to go. Recently I heard someone say, of the current political climate, ‘we should save pessimism for better times’, which I thought was an astute remark.

I would never, ever tell another writer that an ending ‘should’ be hopeful. Some of the most powerful books I’ve ever read – that have galvanised me into a change of heart or a deep psychological response – have had very pessimistic endings, and it’s that very ending which paradoxically creates the possibility of hope in a reader, the understanding that our only hope is to push back against what might seem inevitable. So, I don’t hold a position on what other artists do, and there’s little I dislike more than one writer lecturing another on how they ‘should’ work. But I suspect that my own endings will generally contain at least the possibility of hope, purely because I can’t accept despair as a personal position. I mean, I accept it all the time in my own life, but you have different responsibilities when you put something on the page for others. Maybe.

You interviewed Australian and New Zealand writers for The Writer’s Room while writing The Natural Way of Things. How did these conversations influence the techniques or approaches you tried in this book? How important is it for your writing to speak with other writers about the process and craft of writing? Do you consider it a necessary lifeline for a writer?

It’s a necessary lifeline for me, but I would never presume to say it’s essential for all writers. The one overarching lesson I learned very clearly from the interviews, in fact, was that every writer has her or his own, specific, idiosyncratic and absolutely inviolable process. Part of learning to write, I think, is learning to accept your own needs and nature, and to respect your own instinct and process.

That said, every single interview I did taught me something exceptionally valuable. It was like an amazing private master class each time. When The Natural Way of Things came out I wrote an article for The Guardian where I pinpoint precise lessons I took from specific writers into writing the book.

*

For more from The Writer’s Room, Charlotte Wood’s interview with Lloyd Jones can also be found in The Fuse Box: Essays on Writing from Victoria University’s International Institute of Modern Letters.

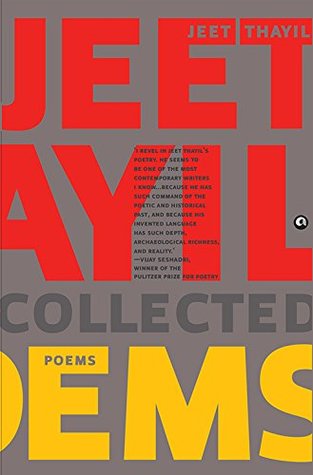

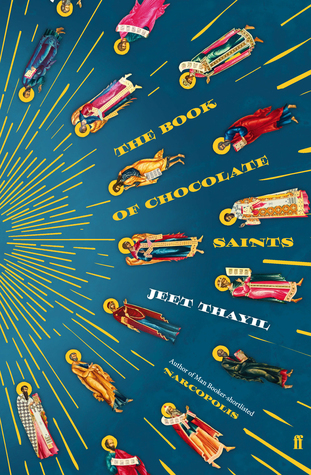

Novelist and poet Jeet Thayil held the first masterclass for this year’s MA. Easily seduced and readily impressed, I drew a picture of him in a cool denim jacket inside my notebook. I also took some notes, which are presented below:

Novelist and poet Jeet Thayil held the first masterclass for this year’s MA. Easily seduced and readily impressed, I drew a picture of him in a cool denim jacket inside my notebook. I also took some notes, which are presented below:

‘This list of ‘tips’ is interesting to me, a little unnerving though, cast as questions and then imperatives. That gives me pause. I hope I didn’t come across as a bully on these matters since uncertainty is a major element in making poems: always a kind of second-guessing which feeds and keeps open the meditative impulse. But I am very grateful to Rebecca for jotting these down, not as dictums so much as just reflections of a fellow traveller of hers-—and anyone smitten with poems and their making. We’re very lucky, aren’t we? And that history is allowing us this moment to support our discussing such matters.’

‘This list of ‘tips’ is interesting to me, a little unnerving though, cast as questions and then imperatives. That gives me pause. I hope I didn’t come across as a bully on these matters since uncertainty is a major element in making poems: always a kind of second-guessing which feeds and keeps open the meditative impulse. But I am very grateful to Rebecca for jotting these down, not as dictums so much as just reflections of a fellow traveller of hers-—and anyone smitten with poems and their making. We’re very lucky, aren’t we? And that history is allowing us this moment to support our discussing such matters.’

It can be, and definitely was with those three books, even though the place in The Natural Way of Things wasn’t a real place but a kind of dreamy (some would say nightmarish!) no-place. I do find that establishing a setting fairly early on helps me develop characters and plot, because once I have a place I can have my people responding to it, pushing against it, and often, being trapped in it with problematic others. Which can bring about useful frictions and conflicts. What I mean is that if I have a place in which to see the people of my story, I really need almost nothing else to begin a novel. This is comforting if, like me, you are the kind of writer who doesn’t plan from the beginning.

It can be, and definitely was with those three books, even though the place in The Natural Way of Things wasn’t a real place but a kind of dreamy (some would say nightmarish!) no-place. I do find that establishing a setting fairly early on helps me develop characters and plot, because once I have a place I can have my people responding to it, pushing against it, and often, being trapped in it with problematic others. Which can bring about useful frictions and conflicts. What I mean is that if I have a place in which to see the people of my story, I really need almost nothing else to begin a novel. This is comforting if, like me, you are the kind of writer who doesn’t plan from the beginning. In your interview with Margo Lanagan for The Writer’s Room you said the scrapbooks she makes for her work appealed to you at a ‘non-verbal, gut level’. You used Pinterest in a similar way to gather images to help you imagine the future world of The Natural Way of Things. What did this approach lend you and how did it influence the tone or language of the book?

In your interview with Margo Lanagan for The Writer’s Room you said the scrapbooks she makes for her work appealed to you at a ‘non-verbal, gut level’. You used Pinterest in a similar way to gather images to help you imagine the future world of The Natural Way of Things. What did this approach lend you and how did it influence the tone or language of the book? I don’t know about you, but I feel that a huge part of my life, and my ‘selfhood’ for want of a better word, exists on some other plane than the visible and the tangible. Our thoughts, memories, dreams, anxieties, our relationships, our sense of ourselves, often have very little to do with what can be identified as the ‘real’, concrete world.

I don’t know about you, but I feel that a huge part of my life, and my ‘selfhood’ for want of a better word, exists on some other plane than the visible and the tangible. Our thoughts, memories, dreams, anxieties, our relationships, our sense of ourselves, often have very little to do with what can be identified as the ‘real’, concrete world. It’s helped, sometimes, to have this idea of a technical mark to aim for. With The Children I wanted to push myself on the drama side of things, to get a bit more suspense and tension into my work. Animal People was the one-day experiment, and in The Natural Way of Things I wanted to play around with reality, allowing myself some speculative, non-realist experimentation. With my new work in progress I’m having a shot at a more complex and rather old-fashioned use of omniscience or shifting points of view, but I don’t think it’s working very well. We shall see! Sometimes the technical and craft elements of writing are consoling things to focus on when other parts aren’t working.

It’s helped, sometimes, to have this idea of a technical mark to aim for. With The Children I wanted to push myself on the drama side of things, to get a bit more suspense and tension into my work. Animal People was the one-day experiment, and in The Natural Way of Things I wanted to play around with reality, allowing myself some speculative, non-realist experimentation. With my new work in progress I’m having a shot at a more complex and rather old-fashioned use of omniscience or shifting points of view, but I don’t think it’s working very well. We shall see! Sometimes the technical and craft elements of writing are consoling things to focus on when other parts aren’t working.