It’s so wonderful to be launching this completely engrossing and fiercely eloquent novel with you all. As many of you know, Claire has been writing for a long time, publishing occasionally but this is her breakthrough and it’s been worth the wait. I also reckon that as a comparative late starter, Claire has written a novel which carries the gifts of those years. I don’t mean that Claire is now some infinitely wise person who knows everything and for whom things are settled. Actually I mean the opposite—Dice is a novel made of uncertainties, of competing viewpoints, of contradictions and inconsistencies. I think it’s the sort of novel you write when you’ve seen enough of the world to understand the otherness of other people.

As a work of fiction, it’s hugely and excitingly ambitious—a multi-voiced portrait of a society really. There are twelve main characters in this book. That’s a lot! Claire’s writing must know them all—even those, especially those most distant from her own experience, especially those most morally remote from her own worldview. Otherwise this book would just be a series of confirmations rather than provocations. These 12 characters come from different parts of town, they vary in age, gender, ethnicity, education, inclination. There are also lots of other significant characters—to the extent that, like a Russian novel from the 19th century, the book has a helpful list of names in the front. It’s a populous story for the very good reason that it needs to be faithful to its subject matter, which is communal and messy and utterly fascinating; namely, what is a jury?

If you’ve glanced at the book, you’ll know this is a novel about a jury in a case involving a group of high school boys charged with sexual assault and rape. It is a procedural crime novel to the extent that it takes us through, in a compelling way, the mechanics of the court room, the often bewildering choreography of the Law and its professional players (defence lawyers, prosecutors, judge, court workers). It’s a world, in effect, seen twice, first through the notions we’ve gathered from film or television and then through the fresh encounter of our senses: here’s one juror looking at the Crown Prosecutor: ‘The man was small, and younger than Eva expected; she knew it was a stereotype but she’d thought the prosecutor would have more gravitas.’ That’s just a tiny moment of mental correction a character has to make near the beginning of the trial but it sets up a pattern of second takes, of people having to look again at what they thought they knew.

Because thrown into this intricate and arcane performance by the court professionals is the jury—necessarily a bunch of amateurs (you and me!) tasked with playing their role in front of a public audience—Are we in a play? wonders one juror. Of course their role is to decide things. And here Claire brings all her deep research and insight into how juries behave, helping the reader understand the strangeness of this deciding and the myriad ways justice is squeezed and shaped by pressures way beyond the facts of a case. This is a situation in which people aren’t just calculating guilt and innocence but how to cover the dishwashing shifts they’re missing at the restaurant where they work, or how to process what happened to them years ago on a date that went wrong, or how to speed things up so they can get overseas to pick up their firefighting deployment. Jury duty then as annoyance and interruption, but also as triggering and profound and, well, dicey. I think that title Dice moves beyond naming the sex game the high schoolers play and starts to inflect everything, showing how chancey our lives are when put under stress.

I don’t think there’s ever been fiction which takes us so close to the jury experience. The novel makes us look at the yawns of the jurors—since a court is also a boring place, even when it is deciding people’s futures—it gives us their bodies, their gestures and complaints and tics, and it makes us listen in on the distracted thoughts, the wrong-turns, the irrelevancies of someone’s mental processes as they try to make sense of the stories emerging through evidence and testimony. And again I love the way Claire moves from major to minor and back again. There’s a very good moment during the trial when Bethany, one of the jurors, is trying to get her chewing gum out of her pocket without the scary registrar noticing. And it’s in the middle of quite important and graphic questioning about the sexual assault and a chewing gum pellet falls onto the floor and Bethany reaches down for it and the creepy male juror, Scott, puts his shoe on her fingers, just resting there not pressing but making his point of control. The novel is brilliant at these small improvised moments when the larger patterns of intimidation and indeed rape culture can be revealed in their ghastly ordinariness.

A lot of this novel happens outside that courtroom as we follow the jurors home and into their lives. The crime procedural is burst open by Claire’s lovely detailing of different worlds – the world of a child care centre, the world of a widowed retiree, the world of a failing businessman, the world of competitive swimming. Dice is both claustrophic and wide open.

I was privileged to work with Claire on this novel during her PhD studies, alongside Yvette Tinsley. I learned so much from both of them. From a legal studies angle, I find Claire’s work hair-raising; there’s definitely an activist spirit to this novel. You finish the book believing that things need to change. But because it’s a grown-up novel, you’re also pondering the complexity of the issues and the tangled ways rape myth replicates itself. That PhD involvement was a little while ago now and reading many drafts over those years, you sort of become a bit over-familiar with the material. I wonder if there’s an analogy to working in court a lot, that you begin to have problem-solving and results as your focus and you lose sight of the human realities in front of you. Which is just to say that I was struck this time by what an emotional read Dice is—how beautifully it dramatises the way feeling enters the jury room—both as distortion and clarification. What to do with one’s own personal story, traumatic or not, when thinking about someone else’s story? The frankness with which Claire lets her characters speak, if sometimes only in their own minds, is a startling pleasure throughout the novel. And when one juror, near the end of the book, who has previously been trapped in her own story and silent, finally speaks, it releases an extraordinary sort of knowing which crashes back through the novel, rearranging yet again our assumptions and our judgments. This novel does not let up.

Juries, as Dice shows us, are about stories and storytelling, how we try to convert the mess of the world into a coherent narrative. How hard it is to find the explanatory power to match life’s barely comprehensible developments. Someone stands up and tells us a story about some people and then another person stands up and tells us a different story about the same people. The diligent juror, we see, is the one who starts writing. Writing notes, writing details, writing to sift and sort, writing about how someone reacts, seems, writing as a way of guessing about others, writing so as not to forget, writing as the beginning of sharing. You won’t forget this novel or the combined fates of all the people in it, and you will want to share it. It turns out that, like all the best novels, the ostensible subject of Dice—juries and how they work—is also the means to pose bigger questions, such as what kind of society do we live in, and how might we imagine a different one, a safer one, a fairer one . . .

Claire Baylis wrote Dice as part of her PhD in Creative Writing at the IIML, Te Herenga Waka – Victoria University of Wellington. She has worked as a jury researcher and legal academic. She lives in Rotorua.

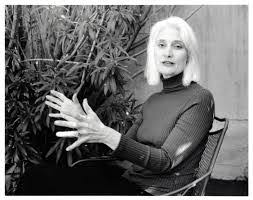

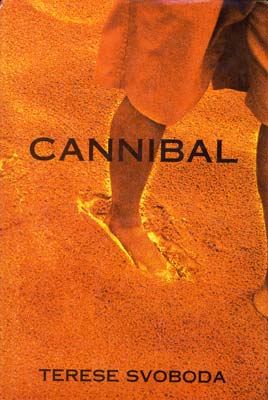

On 16 May, the MA students were honoured to attend a full day masterclass with Terese Svoboda, the author of six novels, a short fiction collection due out next year, seven poetry collections, a book of translation, a biography and a memoir. Her novel Cannibal was named one of ten best westerns of the year and described by one reviewer as ‘a female Heart of Darkness’. Her video work is also award-winning and she’s received a Guggenheim.

On 16 May, the MA students were honoured to attend a full day masterclass with Terese Svoboda, the author of six novels, a short fiction collection due out next year, seven poetry collections, a book of translation, a biography and a memoir. Her novel Cannibal was named one of ten best westerns of the year and described by one reviewer as ‘a female Heart of Darkness’. Her video work is also award-winning and she’s received a Guggenheim. made her want to write fiction. This became Cannibal, her first novel. It was fifteen years in the making, during which time she grappled with some of the differences between poetry and fiction. Poetry occurs in a single moment on a white page, whereas fiction, she was told, emphasised character development and plot, and she was always bored with how to open and close doors in the prose. She says if she weren’t always ‘rebelling against these things’, she would have learned earlier that ‘story is a magical thing that you unearth and discover’ – but magic takes work.

made her want to write fiction. This became Cannibal, her first novel. It was fifteen years in the making, during which time she grappled with some of the differences between poetry and fiction. Poetry occurs in a single moment on a white page, whereas fiction, she was told, emphasised character development and plot, and she was always bored with how to open and close doors in the prose. She says if she weren’t always ‘rebelling against these things’, she would have learned earlier that ‘story is a magical thing that you unearth and discover’ – but magic takes work. A turning point in Terese’s writing life was attending Gordon Lish’s famed writing workshops. She describes these in riveting detail. Lish looked ‘like a Presbyterian minister’, she says, ‘but kind of evil, like Sam Peckinpah’. You weren’t allowed to pee at any point during the sessions, even Terese, who was pregnant at the time. Not only that but the sessions were very long: it wasn’t unusual to finish up at 2am. People would break down, there would be people next to her on respirators, people with two weeks left to live. He made you believe fiction was worth devoting your life to. It was like EST or brainwashing, you emerged believing that.

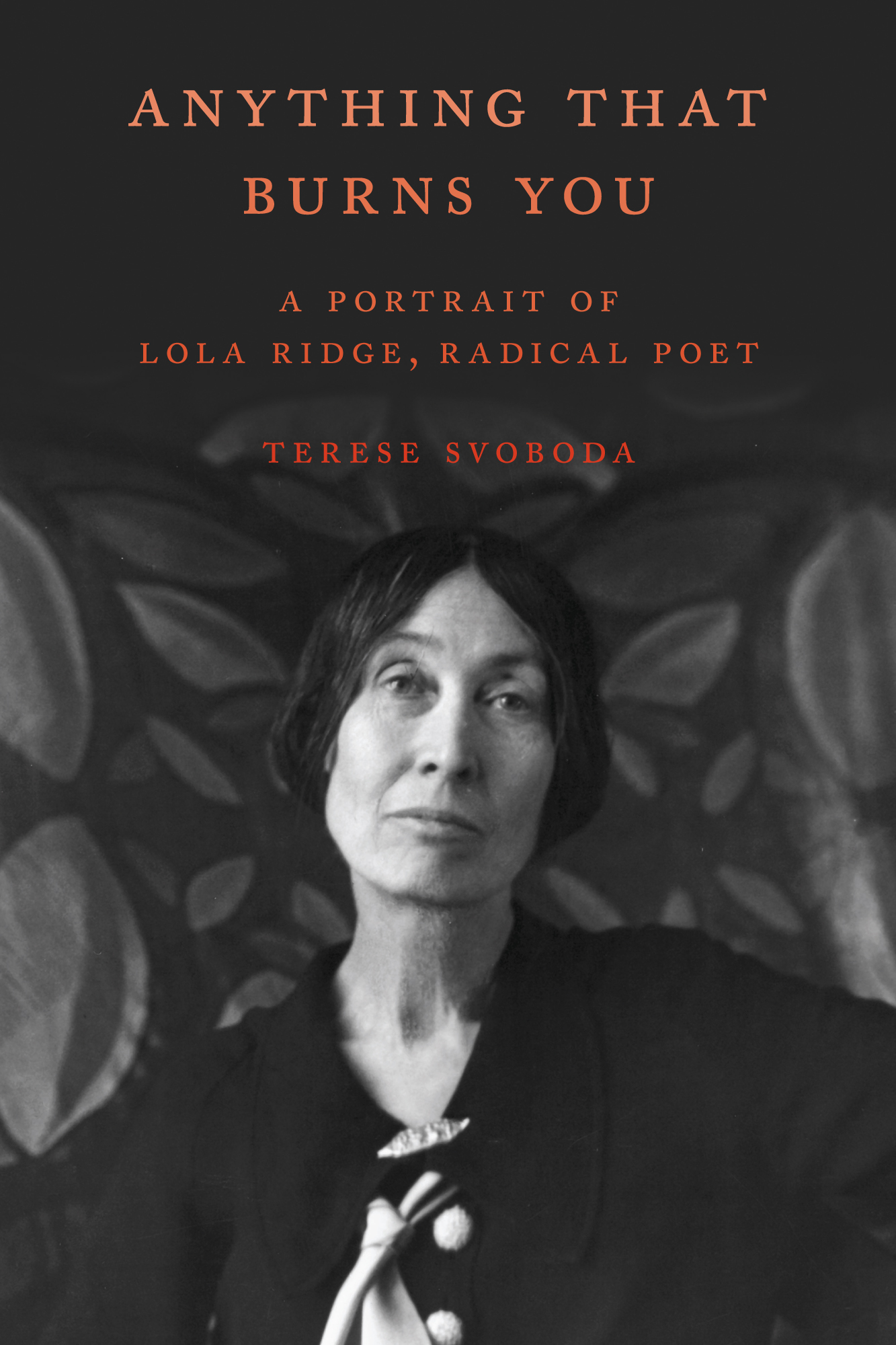

A turning point in Terese’s writing life was attending Gordon Lish’s famed writing workshops. She describes these in riveting detail. Lish looked ‘like a Presbyterian minister’, she says, ‘but kind of evil, like Sam Peckinpah’. You weren’t allowed to pee at any point during the sessions, even Terese, who was pregnant at the time. Not only that but the sessions were very long: it wasn’t unusual to finish up at 2am. People would break down, there would be people next to her on respirators, people with two weeks left to live. He made you believe fiction was worth devoting your life to. It was like EST or brainwashing, you emerged believing that. Terese wrote a biography of Lola Ridge, an anarchist Modernist poet and committed activist. Her second book was from the point of view of a little Australiasian bad girl. She was born in Dublin and emigrated to New Zealand as a child and spent 23 years here before emigrating to New York City, where she received very favourable critical attention as a writer and was an editor at avant garde literary journals. She had a personal relationship with all the big names in New York at that time (between the wars): Marianne Moore was one of her best friends. At her death, the New York Times declared her “one of America’s most important poets.” Despite this, she’s been largely forgotten in New Zealand and the United States. Why is that? Part of it has to do with the politics of the canonisers, Terese argues. Influential Elliot and Pound were elitist, whereas Ridge was vocally and uncompromisingly for the radical left. Women poets were also perceived as a threat during the time Ridge was active, following the immense publishing success of Edna St Vincent Millay. As a result, women poets were widely denigrated. She was also experimental at a time when poets looked for form. Others have seen her perspective with regard to her radical interests in those who were lynching or executed as ‘maternal’, but Terese argues that Ridge always writes from a female point of view and that’s so rare it’s seen as maternal.

Terese wrote a biography of Lola Ridge, an anarchist Modernist poet and committed activist. Her second book was from the point of view of a little Australiasian bad girl. She was born in Dublin and emigrated to New Zealand as a child and spent 23 years here before emigrating to New York City, where she received very favourable critical attention as a writer and was an editor at avant garde literary journals. She had a personal relationship with all the big names in New York at that time (between the wars): Marianne Moore was one of her best friends. At her death, the New York Times declared her “one of America’s most important poets.” Despite this, she’s been largely forgotten in New Zealand and the United States. Why is that? Part of it has to do with the politics of the canonisers, Terese argues. Influential Elliot and Pound were elitist, whereas Ridge was vocally and uncompromisingly for the radical left. Women poets were also perceived as a threat during the time Ridge was active, following the immense publishing success of Edna St Vincent Millay. As a result, women poets were widely denigrated. She was also experimental at a time when poets looked for form. Others have seen her perspective with regard to her radical interests in those who were lynching or executed as ‘maternal’, but Terese argues that Ridge always writes from a female point of view and that’s so rare it’s seen as maternal.